On a summer morning in Incheon, the Global NIP Update project team from the Green Growth Knowledge Partnership (GGKP) visited the Korea Environment Corporation (K-eco) for a formal interview on Korea’s experience with persistent organic pollutants (POPs). The discussion, part of the Global Development, Review and Update of National Implementation Plans (NIPs) under the Stockholm Convention, highlighted the evolution of Korea’s POPs management system and the lessons it can offer to countries with more constrained capacities.

Institutional Architecture of POPs Management in Korea

Inside K-eco, GGKP team sat down with Manager Kim Hyeon-Jin and Assistant Manager Kwon Young-Mook. Young-Mook Kwon, who works within the POPs Monitoring Division, is responsible for conducting nationwide measurements and analysis of POPs as part of the country’s monitoring network. Hyeon-jin Kim, from the POPs Emission Source Investigation Division, focuses on national dioxin emissions, performing inventories of unintentionally produced POPs (UPOPs) such as dioxins, Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and Hexachlorobenzene (HCBs). She explains that Korea, as a Party to the Stockholm Convention, is required to report dioxin emissions annually—an obligation that her division helps fulfill by inspecting facilities and ensuring compliance with national emission limits.

As the conversation unfolds, it becomes clear that Korea’s institutional arrangement for POPs management is both structured and collaborative. The Ministry of Environment (ME) leads on policy development, management, and oversight. The National Institute of Environmental Research (NIER) houses technical experts and is responsible for establishing and updating analytical standards. K-eco, in turn, executes much of the fieldwork—carrying out monitoring activities, generating emissions inventories, and supplying the data that inform policy decisions. When testing is conducted, it is done in accordance with the analytical standards developed and regularly revised by NIER, which also oversees technical guidance to ensure consistency across institutions.

The Evolution of Korea’s Chemicals Legislation

Reflecting on how far Korea has come, interviewees recalled the country’s early steps in chemicals governance. The Toxic Chemicals Control Act, Korea’s first major regulatory framework on hazardous substances, was passed in 1990 and enacted on February 1991. Over time, a series of public health incidents—including the humidifier disinfectant tragedy in 2011 and the hydrofluoric acid leak in Gumi in 2012—underscored the need for stronger legislation. These events catalyzed the introduction of more comprehensive laws, such as the Act on the Registration and Evaluation of Chemicals (K-REACH) and the Chemicals Control Act in 2015, followed by the Consumer Chemical Products and Biocides Safety Act in 2019.

For POPs specifically, the adoption of the Stockholm Convention in 2001 led to the enactment of Korea’s own Act on POPs Control in 2007, which came into effect the following year. Similarly, for mercury, South Korea signed the Minamata Convention in 2014, ratified it in 2019, and brought it into force in 2020, incorporating its management into the existing legal framework. Together, these laws have enabled rapid institutional progress despite limited initial resources.

NIPs and Basic Plans: Planning for Impact

In terms of planning and implementation, Korea maintains a dual system. The NIP is submitted to the Stockholm Convention Secretariat and fulfills international obligations. Domestically, however, the country operates through a series of Basic Plans, which are five-year strategies mandated by national law. The first Basic Plan, from 2012 to 2016, established the POPs monitoring system and created a national response mechanism for the Convention. The second plan, covering 2017 to 2020, continued this momentum, while the third plan, currently in place for 2021 to 2025, further expanded the scope by including mercury.

Each Basic Plan assigns specific tasks to relevant agencies—whether the Ministry, NIER, or K-eco—and implementation is reviewed at the end of each cycle. Any shortfalls are analyzed and addressed in the next iteration, creating a system of continuous improvement and feedback. The Basic Plans translate the Stockholm Convention’s obligations and national laws into concrete operational frameworks and are instrumental in ensuring continuity of action across political cycles.

A Nationwide Monitoring Effort

The monitoring infrastructure itself is extensive. 31 POPs are registered in Korea’s domestic management law, and Korea is regularly tracking 27 POPs through a nationwide network. Substances are categorized based on how frequently they are measured. Some are part of the regular annual cycle, while others, particularly newly listed or analytically unstable chemicals, are measured every three years to verify their domestic occurrence and significance. These efforts include both legacy substances like DDT and PCBs and more recent additions such as various PFAS.

For UPOPs like dioxins, PCBs, and HCB, K-eco compiles emissions inventories using the Air Pollutant Emission Source Statistics System. Public sector data are generated directly by KECO, while private sector facilities conduct self-monitoring and submit data to NIER. To maintain quality and reliability, a Monitoring Evaluation Committee composed of academic, industrial, and institutional experts reviews any changes to analytical methods or site coverage. NIER also manages national quality assurance, including annual inter-laboratory proficiency testing and technical review of deliverables such as inventory reports and monitoring results. If further guidance is needed, external expert panels may be convened.

Private Sector Engagement and the Role of Voluntary Compliance

Still, enforcement is not without challenges. Except for dioxins, few POPs have legally binding emission limits in Korea. As a result, most data collection relies on voluntary cooperation from industries—particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which may lack awareness or capacity to comply. Conversely, large corporations are generally well-informed and better equipped to meet reporting needs— with knowledgeable staff helping facilities identify potential emission sources, and offering advice on reducing or replacing hazardous inputs and processes. These efforts are supported by the understanding that collected data contribute to national statistics and inventory development, not punitive enforcement. Even so, resistance remains—particularly among SMEs unfamiliar with regulatory frameworks—and K-eco frequently must rely on aggregated rather than facility-level data for inventory development.

Tailored Technical Assistance for Small-Scale Emitters

One of K-eco’s most impactful interventions lies in its technical support programme specifically designed for small incineration facilities—many of which are located on islands or serve small accommodation businesses and frequently exceed permitted dioxin levels. Through this initiative, K-eco provides hands-on assistance by conducting on-site diagnostics, offering technical consultations on emission reduction strategies, and performing pre- and post-intervention measurements to demonstrate effectiveness. These services are offered upon request and are geared toward enabling compliance rather than imposing penalties.

To complement these services, K-eco also organizes an annual training programme, which alternates between in-person and online formats. These sessions typically bring together between 100 and 200 facility representatives and aim to enhance knowledge on regulatory requirements, monitoring techniques, and best practices in POPs control. This model has proven effective because it is underpinned by enforceable legal standards—particularly for dioxins. Without such standards in place, broader engagement would be far more difficult to secure.

The Burden of Precision: Capacity, Cost, and Safety

Even with a mature system, Korea must contend with structural and operational constraints. The cost of monitoring equipment is significant—high-resolution instruments such as gas chromatography/high resolution mass spectrometry (GC/HRMS) units can cost around USD 500,000 and are mostly imported from Japan or the United States. Maintaining this equipment becomes more difficult when manufacturers discontinue models, and the market for spare parts and technical support is limited.

|

|

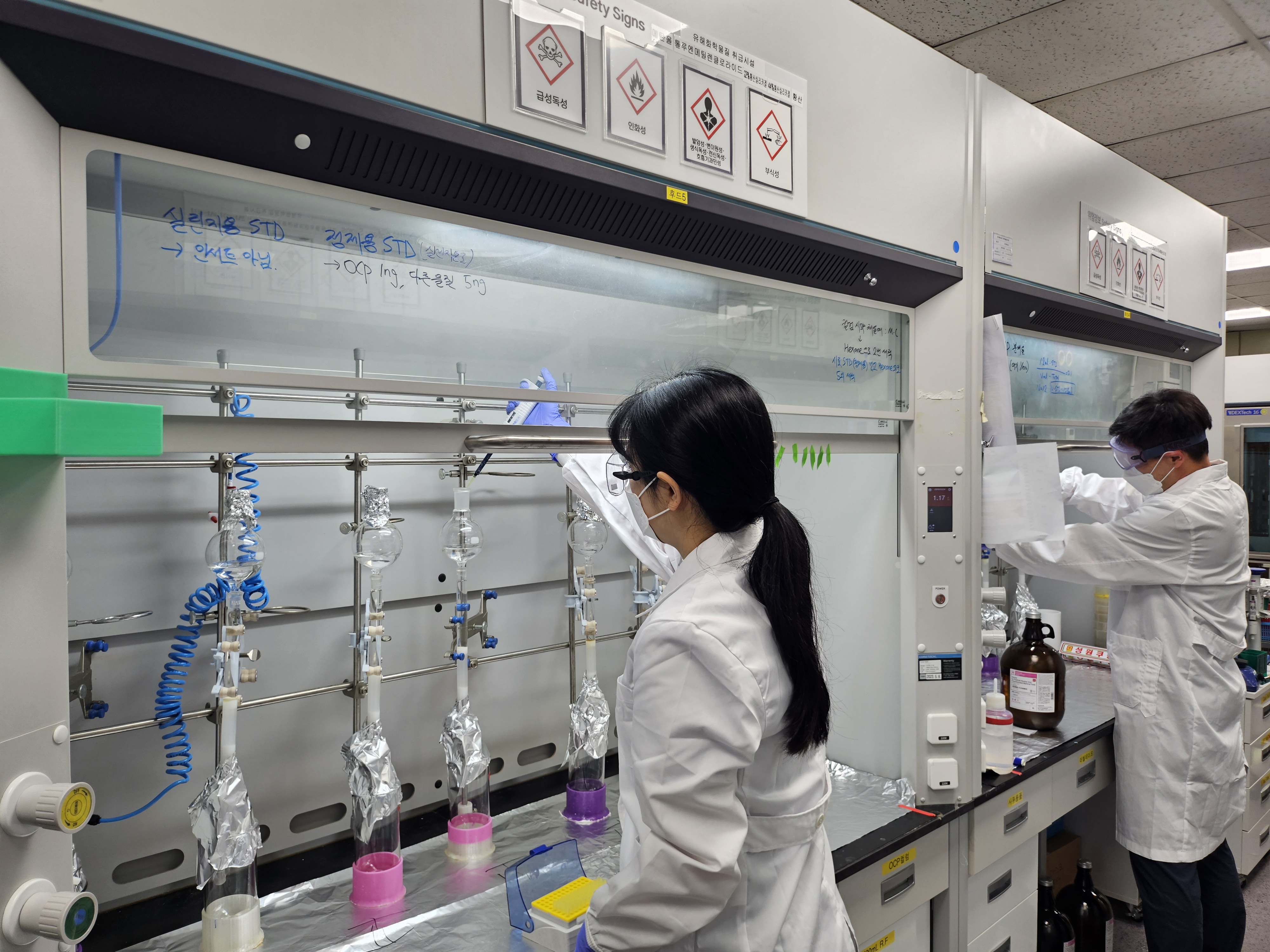

In addition, POPs analysis demands highly trained personnel, and fieldwork is often physically taxing and logistically complex, such as collecting samples from rivers via ships or bridges, or climbing up high smokestacks. Analysts engaging in this work face significant stress due to the toxic nature of standards, risks of bioaccumulative exposure, and the precision required in ultra-trace determinations. Many monitoring tasks involve repetitive manual procedures, and health and safety protocols are strictly followed to mitigate exposure risks during sampling and laboratory work.

PFAS and Human Biomonitoring: Keeping Pace with Emerging Contaminants

The monitoring of PFAS has grown in prominence in recent years, particularly after incidents in the Nakdong River basin. These substances are now part of the national monitoring network and are measured in human biomonitoring surveys conducted by NIER. The fifth cycle of the Korean National Environmental Health Survey included PFAS, PCBs, organochlorine pesticides, and PBDEs in blood samples, with datasets made publicly available via the national Open Data Portal. These data are also shared through press releases and public summaries. Facility-level data, however, remain confidential due to sensitivity and industrial confidentiality protocols.

|

|

Public Awareness and Data Accessibility

In terms of public awareness, POPs no longer command the same attention as in the past. While names like “dioxin” or “DDT” still resonate with the public due to past media coverage—especially in connection with Agent Orange—broader awareness of “POPs” as a category is low. Today, public concern tends to center on climate change or air quality. As such, outreach has shifted toward industrial stakeholders and regulatory communities rather than broad campaigns targeting the public.

Nevertheless, data accessibility remains a key feature of Korea’s system. Journalists and researchers regularly consult datasets released by the Ministry of Environment and NIER, often using them to highlight regional "hotspots" or conduct trend analysis. These inquiries are commonly fielded by Korea’s regional environmental research institutes, which also help contextualize results and provide technical responses to the media.

Lessons for Developing Countries

When asked what has enabled Korea to achieve such rapid progress, the experts point to several factors: clear policy direction and political will; consistent investment in laboratory infrastructure; a strong culture of training and technical skill-building; and, crucially, a five-year planning cycle that enables feedback and course correction. Nevertheless, they are acutely aware of the difficulties facing countries with fewer resources. Many developing countries cannot afford high-end instrumentation or retain skilled analysts due to brain drain. Legal frameworks are often underdeveloped, and industries may not cooperate in the absence of enforceable standards. In some places, even basic environmental infrastructure is still lacking.

In response, Korea engages in international cooperation through forums such as the East Asia POPs Forum, offering training and technical demonstrations to regional experts coming from developing countries. However, both interviewees stress that meaningful capacity-building requires not only knowledge sharing but also investment in core analytical equipment—without which the best training cannot be applied.

As the interview drew to a close, the team reflected on the institutional strength and scientific rigor behind Korea’s POPs management. Beyond technical systems, they were struck by the dedication of the people who sustain them—analysts, inspectors, and managers working quietly but diligently to safeguard environmental and public health.

We would like to extend our deep gratitude to Hong Saerok and Lee Changjoo for their kind support in organizing this interview, and the tour to K-eco ’s dioxin laboratory. This visit also marked the participation of Yeoeun Shim, a K-eco-sponsored GELP intern, who joined the interview team as part of her internship with GGKP, GGGI.

This blog post was developed drawing on insights from the GGKP field visit to K-eco on 19 August 2025. As part of the Global NIP Update project (GEF ID 10785), funded by GEF and led by UNEP, this field visit provided new knowledge and insights from South Korea that would foster peer learning on the development of POPs inventories of partner states.

To learn more about the Global NIP Update project, visit Global NIP Update | Green Policy Platform

한국어로 보기: 한국의 POPs 최전선을 가다 – 한국환경공단 | Green Forum