Curriculum And Syllabus.

Curriculum and syllabus refer to different features of the learning environment:

Curriculum:

A curriculum is a broad term that encompasses the entire educational program of an institution, school, or even a specific education system. It refers to the overall structure of planned learning experiences and intended learning outcomes within an educational institution or programme. A curriculum includes various elements, such as educational goals, learning objectives, teaching methods, assessment strategies, and often guidelines for individual courses. Therefore a curriculum is a very comprehensive term referring to the entire educational program, including multiple courses, their interconnections, and the overall educational goals of an institution or system.

In Wales four general purposes of a school’s national curriculum are the starting points and aspirations for schools to design their own curriculum. The four goals are to support students to become:

ambitious, capable learners, ready to learn throughout their lives;

enterprising, creative contributors, ready to play a full part in life and work;

ethical, informed citizens of Wales and the world;

healthy, confident individuals, ready to lead fulfilling lives as valued members of society.

Syllabus:

A syllabus is a document specific to a particular course in the curriculum, outlining the content and themes for that course. It is a detailed outline of a specific course and typically includes information such as the topics or units to be covered, a schedule of classes, reading materials, assignments, assessments, grading criteria, and sometimes, the learning objectives. In essence, a syllabus provides a roadmap for students and instructors, outlining what will be taught in a particular course. It is specific to a single class and provides a detailed view of the course content and requirements.

A national curriculum for schools is set out in the Welsh Government’s document entitled ‘A Common Understanding’, where ‘Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship’ (ESDGC) is a syllabus to give learners, at all stages of education, an understanding of the impact of their choices as consumers on other people, the economy and the environment. In this context, ESDGC defines Wales’ Syllabus Of Radical Hope, where every school has the opportunity to design and implement their own body of knowledge about living sustainably within the educational framework of ‘circularity’.

Circularity, or the circular economy, is an economic model that follows the three Rs of consumerism: Reduce, Reuse and Recycle. It means that products are created, each with its own end-of-life taken into account. In a circular economy, once the user is finished with the product, its material goes back into the supply chain instead of the landfill or the incinerator.

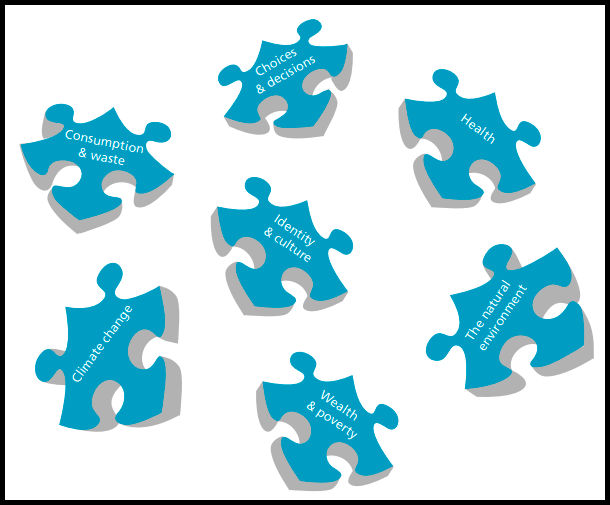

This Common Understanding has been developed from the experiences of Welsh teachers and practitioners who were already involved in addressing seven themes of Wales as an economic island, which, in terms of its carbon footprint, is living beyond its planetary limits.

Unlike a standard jigsaw the themes can be put together in a variety of ways within the circularity syllabus. Therefore, the starting points of individual students may be different, but in time a student’s picture of circularity will contain all the themes of ESDGC, as a personal body of knowledge, and these will be interrelated and interdependent.

Read More